|

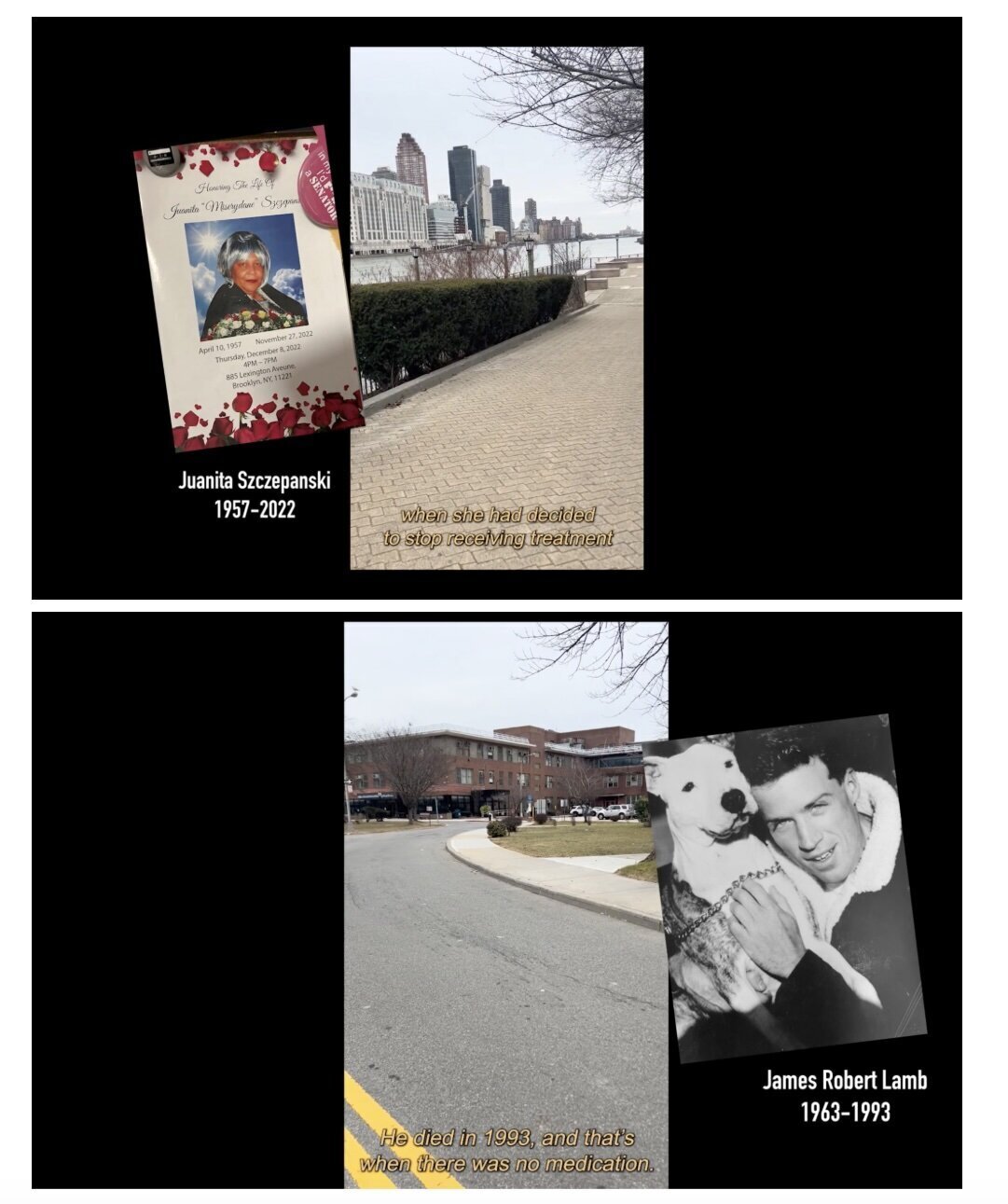

| This piece of writing was shared on Theodore (ted) Kerr’s mailing list on January 13, 2025. Please Hold is a 2025 documentary by videomaker and scholar Alexandra Juhasz in which she grapples with what it means to fulfill the wishes of two friends, at different times, who wanted her to film them before they died. Juhasz is a close friend and collaborator. I saw many drafts of the work while she was in process. I am also in the video, and have seen it many times since its release, including at the premiere, with students from an AIDS history class I teach.It was during one of the more recent screenings that something came to mind: Juhasz is Dorothy. Around the 50-minute mark of Please Hold, the camera pans down and we see that along with Juhasz’s light blue summer dress, with flecks of white, are her shiny red shoes, a late twentieth-century update of Judy Garland‘s blue gingham pinafore and ruby slippers. It is an uncanny visual parallel that welcomes contemplation.An easy reading focuses on Juhasz as a once wide-eyed girl from a flyover state, like Dorothy, who came of age among a larger-than-life community. A more interesting read, as it relates to Juhasz’ Dorothy-ness, and one that grounds us in a reminder that Dorothy had her own story, comes in the form of a question: what does it mean to be central in a narrative of loss, and to keep on going? Death and Video Over the course of Please Hold’s 74 minutes, the viewer joins Juhasz as she shoots first person on her iPhone, walking through New York City, specifically Roosevelt Island, where she spends a bit of time, and the Lower East Side, where most of the video is set, as she recounts her history with the now gentrified area.As Juhasz walks, we watch interviews Juhasz performed with two friends at their request near the end of their lives, which become the heart of Please Hold. On video, we meet James Robert (Jim) Lamb (1963-1993), a white gay theater performer who died with HIV at age 29 in 1993, and Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski (1957-2022), a Black disabled media activist in her sixties, who died on her own terms in 2022 as she dealt with many health struggles.  Lamb, Szczepanski, and Juhasz may seem like an unlikely grouping, a motley mix of Black, white, straight, gay, queer, male, and female, along with many more differences when it comes to class, geography of origin, and more. For other people, specifically those of us within the ongoing HIV response, the trifecta makes perfect sense, in the way Dorothy, the lion, scarecrow, and tin man make sense when one considers the journey they are on. We know that communities within the HIV response are much more diverse than ever pictured. Lamb and Juhasz bonded in college, two young queer people who were doing their best to ensure they had big creative lives. It is Lamb who is with Juhasz in the footage when she is revealed to be a Dorothy. We see Juhasz’s red platform shoes next to Lamb in his shorts and boots. They are standing in front of their apartment door reading out loud slogans from the stickers that they have affixed just below the peephole, communicating their individually specific yet interconnected politics: AIDS Is Not Over, and Keep Abortion Legal. Before he died, Lamb and Juhasz went to Miami together, where Juhasz shot an hour of footage, which she used a decade later in her film, Video Remains. The footage serves as a vehicle to remember Lamb, while allowing Juhasz the opportunity to process the ongoing AIDS crisis and the work of mourning. We meet a group of queer youth of color at an HIV support group, a generation younger than Lamb, who are making their way through their own complexities with HIV, while also hearing female and lesbian AIDS workers talk about the emotional fallout of remembering. Szczepanski and Juhasz met in a video collective that Juhasz started called WAVE, Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise in 1990. Together, with a small group of other women, they made a collection of work about the Black feminist politics of care that while central to the epidemic, mainstream culture was largely choosing not to focus on. In archival footage of Szczepanski, from early WAVE videos that we see in Please Hold, we meet a vivacious and smart woman, as playful in conversation as she was in her video work, seemingly always on the verge of sharing a joke and an epiphany about injustice. Aware of Video Remains and Juhasz’s extensive practice as a videomaker, as well as their decade’s long history of collaboration on AIDS media, Szczepanski, in the final months of her life, asked Juhasz to record a series of conversations with her from her hospital bed. Juhasz agreed, and soon after Szczepanski died, she released I Want to Leave a Legacy: The Video/Activism of Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski. The video weaves together the deathbed interviews with examples of Szczepanski’s impressive and still largely underseen video work. I see Video Remains and I Want to Leave a Legacy as part of an important tradition: AIDS-related deathbed portraits, unflinching and generous images done with love and consent. These are images captured, most often by loved ones, in the lead-up to or moments after death, intended for circulation. I see these portraits as similar to AIDS-related political funerals, where people with HIV requested that after they die, their corpses be used in a public procession, most often to the homes or offices of people whose action (or most often, inaction) led to their premature death. Much of the thinking behind political funerals was inspired by David Wojnarowicz. The Marys, an affinity group within ACT UP, who organized political funerals for Mark Lowe, Tim Bailey, Kiki Mason, and Aldyn McKean, were inspired by Wojnarowicz’s book Close to the Knives, in which he writes, “Every time somebody dies of AIDS, I think their lover, their friends, should drive with their bodies 100 miles an hour down to the White House, and throw their body over the White House fence.” Wojnarowicz famously also wore a black leather jacket to a demonstration in 1988 with the now iconic words he wrote on the back that read: IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA. After photographer Peter Hujar—his friend and one-time lover—died, Wojnarowicz photographed Hujar’s feet, one of his hands, and his face. Upon his own death, Wojnarowicz was photographed by artist, and a mentee, Patrick McDonnell. These photographs circulate far less than anything else that either of these highly regarded and dearly missed artists produced, and yet, when seen, cannot be forgotten. Knowing someone is dead is a different experience than seeing someone upon death. Facing death, as Juhasz’s videos make clear, is not easy, and leaves a witness with a visceral sense of a person’s life, and also, how much they will never get the chance to experience after the camera is put away, and the life ends. For artist AA Bronson, it was on him to take the deathbed portraits for General Idea, the art collective he was in with Jorge Zontal and Felix Partz, both of whom died in 1994 with HIV. The image of Zontal is an intentional reference to the Holocaust, and was taken a week before he died. As Bronson has recounted, “Jorge’s father had been a survivor of Auschwitz, and he had the idea that he looked exactly as his father had on the day of his release. He wanted to document that similarity, that family similarity of genetics and of disaster.” The portrait of Felix was taken mere moments after his death. The viewer finds him, as Bronson did, eyes open, amidst a riot of color and shapes. Importantly, Bronson also created his own deathbed portrait, an acknowledgment that with General Idea being over, he was also experiencing a death of sorts. Entitled AA Bronson, August 22, 2000, the work is a sarcophagus-like wooden chest with a life-size black-and-white photo of the artist, laid out like a body in a tomb, naked, mounted on the lid. Similar to the General Idea death portraits, Video Remains and I Want to Leave a Legacy are importantly collaborative in nature. Facing the loss of life, Lamb and Szczepanski reached out to Juhasz in their own ways, asking for an opportunity to speak either their ideas for a future that may never come, as Lamb did on a beach, or impart lessons to the next generation as Szczepanski did from the hospital. Just as Dorothy followed through on her commitment to bringing her friends to Oz, Juhasz fulfilled her promise too, twice. A difference, of course, is that at the end of the movie, Dorothy is the one who leaves. When it comes to Juhasz, she is the one who remains. What does it mean to be the one behind the camera? Or rather, what comes after death for the living? Is Please Hold Juhasz’s version of Bronson’s tomb, or is it something else? Threshold of Life In 2022 Juhasz and I published a book about AIDS, memory, and culture. I planned our launch party to be held at a bar on the Lower East Side, The Parkside. Unknown to me, Juhasz and Lamb had lived decades earlier on the same block. In fact, in Please Hold we see The Parkside in the scene leading up to Lamb, Juhasz and their apartment door. No place like home, indeed. I selected The Parkside because of my connection to our friend Elizabeth Koke, who we know from doing AIDS work, and her partner and our friend Gavin Downie, who owns the bar. Both are in the video. Koke, Juhasz, and I are part of a collective called What Would an HIV Doula Do? And even though Downie is not a member, he is very much an HIV doula, which we understand as a person who holds space during time of transition, and that HIV is a series of transitions that start long before a diagnosis, and continues after death. In Downie’s possession, as we learn in Please Hold, is a collection of gay pornography he inherited from a friend and bar regular who lived with HIV. As Koke recounts, Downie believes “a place is not a real gay bar unless you have taken care of someone while they are dying.” These collisions of place, relationships, and HIV across time are heady fodder for Juhasz. In the video, we witness Juhasz working to make sense of what it means to be the one to shoot the footage while her friends are still alive, and then to make and circulate the videos after they have died. The process of grief comes out in what she and others are saying on tape. It also emerges in form. In the video, the walk to the bar goes from what could be a linear path to one that mirrors the work of memory, loss, and healing: it doubles back, new information is shared, while stories get repeated. Towards the end of the video, in an interview Juhasz conducted with me well into the editing process, I share an epiphany I had while watching all the cuts: “ you are trying to record the thing you are willing to release. .. that echoes what Jim was asking, even if he wasn’t aware. He was asking to be released. And Juanita knew she was doing that… asking to be recorded to be released.” It seemed important to name that as much as the videos were about dying, they were also about the living. As Juhasz has mentioned to me in conversation, for her this commitment to living means, “we continue to learn and grow through mourning and engaging with the dead.” Months later was when I had the next epiphany, the one where I noticed the red slippers. I sat on it for a while, not knowing if it was worth sharing. On a subway ride I remembered an interview I read years ago with director James Mangold. He talked about how when writing a script, he looks for a parallel fable, a template to hang his story. For the film Girl, Interrupted, a story about a young woman committed to a mental health facility, his primary text was The Wizard of Oz. He was moved by writer Salman Rushdie’s summary of the story: “The Wizard of Oz is a film whose driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults, and how the weakness of grownups forces children to take control of their own destinies and so, ironically, grow up themselves.” That unlocked for Mangold a Freudian reading of the movie: “Everyone in The Wizard of Oz is missing some part of their psyche: missing courage, missing love, missing smarts.” Facilitating their journey to get back what they are missing is Dorothy. She delivers them to the wizard, and their release from suffering. While I watched the various drafts of Juhasz’s film, I was often perplexed as to the purpose of Please Hold. Why was she making the movie? She had honored her loved ones by capturing them on video before they died and then memorialized them through production, distribution, and circulation of her two death bed videos made from the footage.It was thinking about Juhasz as Dorothy that unlocked the answer. Dorothy has needs. She is not following the yellow brick road only for the Lion, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man any more than Juhasz made the deathbed videos only for Lamb and Szczepanski. Please Hold is the very necessary finale in a trio of videos that include Video Remainsand I Want to Leave a Legacy. Mangold points out that one of the lessons in The Wizard of Oz is that figuring out what we need does not have to be a big journey. It can be as immediate as looking inside oneself. To get back to Kansas, for example, all Dorothy has to do is click her heels and speak her truth. Video Remains and I Want to Leave a Legacy were projects primarily about Lamb and Szczepanski and their deaths, fulfilling their wishes to be seen and remembered. Please Hold is Juhasz standing firm, in her red shoes, not in an effort to go home. Instead, it is her way to name and grapple in public with grief and the responsibility of bearing witness and how that isn’t resolvable, over when done once. How it changes if one lives on. Please Hold is her version of Bronson’s tomb, yet instead of marking a death in order to move on, Juhasz is marking life and life (unlike death) is structured by change, movement, repetition, growth. The video ends with a door opening to The Parkside, and a community of friends—and ghosts—waiting for her just beyond the threshold. |

|

Related Links Organize a screening of PLEASE HOLD Learn more about Political Funerals Listen to this podcast about Political Funerals that includes Juhasz Here is the James Mangold inteview Here is the Salman Rushdie book on The Wizard of Oz As part of Juhasz’s distribution strategy, she organized a series of exhibitions, HOLDING PATTERNS, one in LA and one in NYC and one inBoukder, CO. For more information on Lamb and Szczepanski, check out Video Remains and I Want To Leave a Legacy and Jim on the Beach. |